At the start of my coaching journey I had a firm, clear idea of what my players wanted – needed – from me as their coach. Nowadays I have a good idea, too – but it’s not the same thing, and I know that it will vary from one player to another.

Is any coach an expert?

It seems that when most people go into football or cricket coaching in the UK they start from a position of assumed expertise.

Coaches, parents and many children look to the coach as the font of all knowledge around the sport they are coaching. Most coaches will have played a bit as kids or adults themselves – some to a very high standard. Almost all of them will have watched lots of matches on the telly. And they’ll probably have read, heard and talked around their subject for thousands of hours over many years.

Does that make them experts? Yes, in most cases it probably does.

Does it make them ideal coach material? Perhaps. Not necessarily.

Does their expert subject knowledge and years of experience of playing (and, presumably, having been coached themselves) mean they are automatically expert coaches at football or cricket coaching (or any other sport)? No, it doesn’t.

Does it mean they know what the children they’re coaching want? No, it doesn’t.

Coaching is not knowledge transfer

Transferring knowledge from one person to another is not coaching. Explaining by word or action how to perform a technical skill is part of coaching – but only a very small part, in my opinion. Your in-depth knowledge of the biomechanics of a textbook cover drive in cricket is virtually worthless in terms of the role it is likely to play in creating the next Ian Bell. Likewise, explaining the role of different parts of the feet in dribbling with a football won’t, on its own, create the next Lionel Messi.

I’ve explained both those things to the children I coach at cricket and football. And I’ll keep doing them. But I know they’re only a small part of the job. How do I know? Because I’ve asked the children themselves.

What do kids want from sport?

Ask parents why they want their kids to play sport and you’ll get a variety of replies. In football, you’ll hear a lot of “I want him [or her] to play at the highest level they can”. That’s Dad code for “I want him [or her] to be a pro and play for England [or other country]”.

I hear less of that with cricket parents, and more reasons that they share with the other parents in football: “I want them to be fit and active”, “I played the game myself and love it so I want them to love it to”, “I want them to learn to compete”. All reasons that I’m not going to argue with. But the point is, there is no single reason.

Ask the children themselves, and you’ll get even more variety. The FA, among others, have done extensive surveys on why young people play the game and the reasons given by kids may surprise a lot of parents. The top six reasons were:

- Trying my hardest is more important than winning

- I love playing football because it’s fun

- It helps keep me fit and healthy

- I like meeting new friends through football

- It’s a really good game and I love it

- I like playing with their friends

Ask your players why they play the sport, and you’ll probably get similar answers. I know I have.

What do we want as coaches?

But we want our kids to develop, right? Like those Dads, we want them to play at the highest level they can. We want them to fall in love with the game. We want them to star for our senior team; we want them to become well-rounded adults; in truth, we may have as many reasons for coaching as the kids do for playing.

But, let’s face it, it’s not about us. The only person who can make a child turn into an expert player of that sport is the child themselves. Parents, schoolteachers, coaches all help, definitely (and I can’t over-value the role of parents), but you’re not going to create the next Virat Kohli or the next Leo Messi working with a child for a couple of hours a week.

How do children develop?

As I said in a previous post, I believe the best thing coaches can do is inspire children to play the game and want to get better. Once we’ve got that commitment and that buy-in, that’s when our expertise becomes important.

Children learn through experience, through trying things out, through play. Expertise comes from lots and lots of that happening – in games with mates round the park, in games during break at school, playing in the street after school (not that that happens much any more).

In other words, to develop into a top-level cricketer or footballer you will need to practise for hours and hours and hours.

How do we get that commitment? To my mind, it’s a sales job. You need to sell them the game before you can get them to put the hours in at doing it, because they’ll only do it if they want to do it.

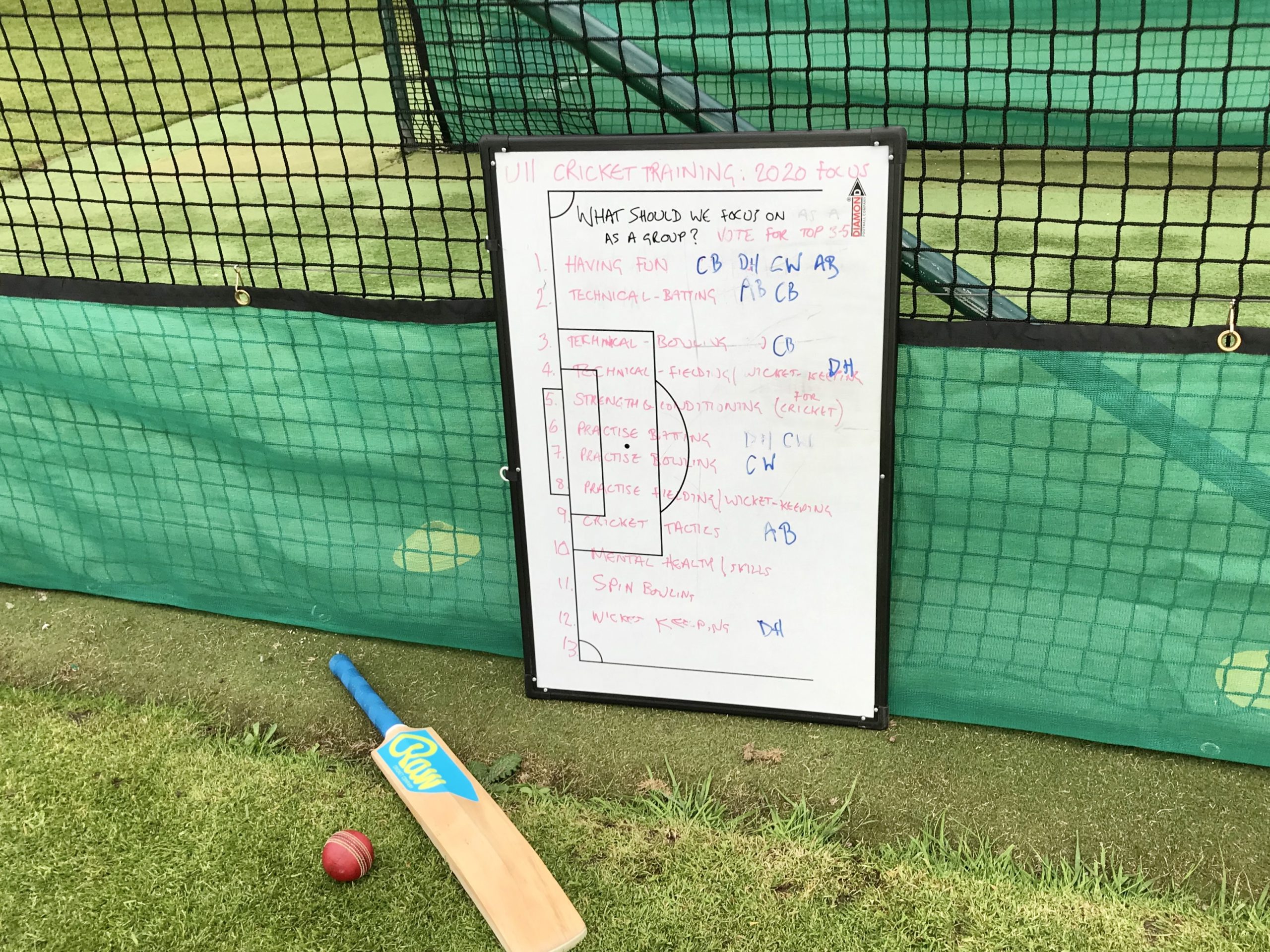

And as any good salesman will tell you, to sell someone something you first need to understand why they might want it. Which is why finding out what your players want is so important.

The other thing to note is that what players want will change over time: so it needs to be something we do regularly and repeatedly.

One day, perhaps, I’ll hear that what a player wants is my expertise. But until then, I’ll carry on doing what all good salespeople do: find out what your customer wants, and give them it.