Brazil’s fourth goal in the 1970 FIFA World Cup final, scored by their captain and right-back Carlos Alberto, is widely regarded as one of the greatest football goals of all time. It has fascinated me for years so, as Britain went into another lockdown and grassroots football was suspended, I spent some time analysing it.

I wanted to capture exactly why I have always found the goal mesmerising. But I also wanted to look at how it came about, and whether Italy, Brazil’s opponents, could have done anything differently to stop it. Was Carlos Alberto’s goal “football from outer space”, was it the result of Italian tiredness, was it bad defending – or a mix of all three?

If you aren’t familiar with the goal – or just want to see it again – here it is. The video starts with Italy in possession in their own half, and ends 47 seconds later with the ball in the back of the their net.

Background to the goal

Brazil’s 1970 team has a strong case to be regarded as the greatest international team of all time. Manager Mario Zagallo had a wealth of riches at his disposal, although he still had to work to mould individual talent into a team. Notably Gerson, Roberto Rivelino, Tostão, Jairzinho and Pelé all played as number 10s for their clubs.

With Pelé the undisputed 10 in a Brazil shirt, Zagallo asked Rivelino to play on the left of midfield, while Tostão played as a roving number 9. Jairzinho was asked to play on the right but with licence to leave his allocated spot to fill in where he might be needed.

In effect, Brazil were playing Total Football four years before the Dutch popularised the idea. Players were free to move positions to create numerical superiority in one area and space in another. This would be critical in Carlos Alberto’s goal in the final.

The final finished 4-1 to Brazil, suggesting that it was something of a mismatch, and perhaps it was. Italy had endured a tough semi-final against West Germany and this, together with the Mexican afternoon heat and altitude, has often been used to justify their obvious tiredness in the closing stages of the match. But they were also the reigning European champions at the time, with players who had enjoyed European Cup success with their clubs, and a reputation for defensive solidity and being difficult to break down. Their national side, like their top club teams, used a catenaccio system based on a libero, or sweeper, playing behind four man-marking defenders. This, too, would be a critical factor in Carlos Alberto’s goal.

Building from the back: Tostão to Clodoaldo

The video begins with an Italian attack. 85 minutes have gone and Italy are 3-1 down. Midfielder Juliano takes the ball down the right flank but is dispossessed by Tostão, who has tracked back from his centre-forward berth.

Having won the ball, Tostão plays the ball back to Brito on the edge of the Brazilian penalty area. The stage is set.

Brito passes to Clodoaldo, who takes part in a triangle of passes with Pelé and Gérson before getting the ball back.

Breaking lines: Clodoaldo to Jairzinho

Next comes the first bewitching part of the move. From his original unpromising position Clodoaldo dances through the Italy midfield, taking four Italians out of the game. It is an unfussy, almost businesslike dribble; there is no exaggerated flair or trickery, just the feints and fakes of a player so practised to the point of greatness in the art of staying on the ball and protecting it under pressure that it looks natural.

Having broken the Italian’s midfield shape, Clodoaldo passes short to Rivelino on the left touchline. Rivelino plays a firm vertical pass up to Jairzinho, who has moved across from the right to the left wing position. Despite the attentions of a defender – Inter’s Giacinto Facchetti – the pitch now looks massive, with acres of space in front of the Italian defence.

The final third: Jairzinho, Pelé and Carlos

The rest of the move has gone down in history. Jairzinho cut inside onto his right foot and sprinted with the ball, leaving Facchetti behind. Before the covering defender could challenge him he played a pass to Pelé, stood in a withdrawn number 9 position.

Pelé languidly turned, paused, and, as Carlos Alberto steamed into the space on the Brazil right, “rolled the ball into his path with the relaxed precision of a lawn bowler”, in the words of sportswriter Hugh McIlvaney. Carlos Alberto hit the ball without breaking his stride and it rifled past the Italian keeper into the bottom corner of the net.

Analysis

Most casual observations about this goal focus on Pelé’s pass and the pausa, or pause, that preceded it, and the fact that all bar two of Brazil’s outfield players played their part in the build-up. Attention is also rightly paid to Clodoaldo’s leisurely dribble that so distracted Italy’s midfield.

Italian defensive problem #1: Facchetti

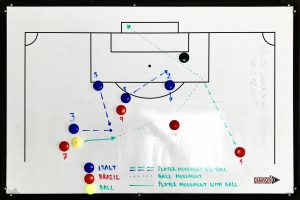

More serious analysis tends to highlight Jairzinho’s position on the left wing and the fact that Facchetti has followed him. As diagram 1 below shows (Jairzinho is the red 7 and Facchetti the blue 3), this left Italy exposed to an attack on Brazil’s right flank.

It seems scarcely credible that Facchetti – Italy’s captain and arguably the best left-back in the world – would commit so wholeheartedly to man-marking his opposite number that he would follow him all the way across to the other side of the pitch. It seems all the more incredible when you consider that Facchetti himself had attacked down the wing for his club, Inter, for years. So it couldn’t have been totally unexpected, even in pre-video days, that a full-back could have joined the attack as Carlos Alberto did.

We don’t know exact team instructions but even within the rigid Italian man-marking system of the time it seems naïve of Facchetti to get suckered into following Jairzinho so far. By comparison, Burgnich and Bertini shared the marking of Pelé in the match, with Burgnich marking him when he played in a forward position and Bertini picking him up when he dropped deeper. So why couldn’t Facchetti have handed Jairzinho to one of the other defenders?

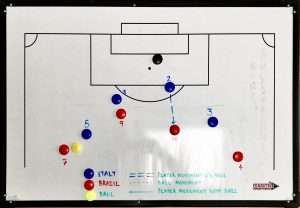

Italian defensive problem #2: Burgnich

The key to this goal may lie in Bertini’s substitution for Juliano, a more attacking midfielder. Without Bertini Facchetti may have simply had nobody to hand Jairzinho on to. Burgnich now had sole responsibility for Pelé and Rosato was marking Tostão. Juliano – the final player to be flummoxed by Clodoaldo’s dribble – didn’t have time to get back before Rivelino fired his pass forward to Jairzinho.

It may also help explain Burgnich’s failure to close Pelé down.

Without Bertini Burgnich was confronted by a dilemma centre-backs still face today with forwards who drop off into “hole” between the defence and midfield.

Should they push up and deny the forward any space to work with, at the cost of leaving space in behind them, or do they stand off and risk giving the forward room to dictate the play? Burgnich chose the latter option.

It seems the wrong choice, given that he should have in theory been able to rely on Cera, the defensive libero, to sweep up any balls played in behind him. But as Bertoni had picked up Pelé when he dropped deep it may be that in that crucial split-second – Pelé’s pausa – Burgnich’s thinking hadn’t quite caught up with the game.

So while Pelé’s pausa before playing his pass to Carlos Alberto is, clearly, a thing of beauty, there’s no doubt that Burgnich made it easier for him.

To be fair, it’s 85-minutes in, it’s nearly 2pm in Mexico City in June, and the Italians have been run ragged by some of the best attackers in the world; it’s hardly surprising if some mental tiredness has crept in.

Italian defensive problem #3: Cera

Finally I want to consider Cera, the sweeper.

The point of a spare man in the Italian system was to sit behind the man-markers and pick up either any loose balls that were played behind them or cover them if they were beaten one-on-one.

Cera does neither of those things. He does the opposite to Burgnich: he races out to close Jairzinho down, possibly because he realises Jairzinho has done Facchetti for pace. And it’s Jair’s split-second acceleration that finally kills off any defensive shape that Italy had remaining.

Or, rather, it’s the alternating between quick and slow play – like the torture technique of waking a prisoner up every time they drop off to sleep.

Brazil’s midfield start it, with the slow-slow-quick build-up of passing followed by Clodoaldo’s run; the drop in tempo followed by Rivelino’s pass, another drop before Jairzinho cuts inside, then the final adagio movement by Pelé before Carlos Alberto’s killer blow.

Alternative solutions

Could Italy – as tired as they were by this point – have prevented the goal?

It’s possible, given that before Carlos Alberto’s arrival they had a 4v3 overload – Facchetti on Jairzinho, Rosato on Tostão, Burgnich on Pelé and Cera spare. The issue is their shape, or lack of it, by the time Jairzinho turns inside and hits the afterburners. Their rigid man-marking was incompatible with Brazil’s movement and interchange of positions.

I have heard it said that this goal sounded the death knell for man-marking defensive systems. It certainly didn’t – twenty years later West Germany won the 1990 World Cup using three man-marking defenders and a sweeper – so where, apart from their obvious tiredness, did the Italians go wrong?

The end of catenaccio?

Not long after this goal, Italian teams began to adopt the Zona Mista system. Using Zona Mista Italy would win the World Cup in 1982, Juventus would enter their most successful period on the European and World Club stage, and West Germany would win that 1990 World Cup. It was a formation that mixed the player-orientated focus of man-marking with the ball-orientated flexibility of zonal defending.

In other words, defenders would mark whichever player was most appropriate within their zone. If a player moved out of their zone and into a teammate’s, the teammate would mark the player instead.

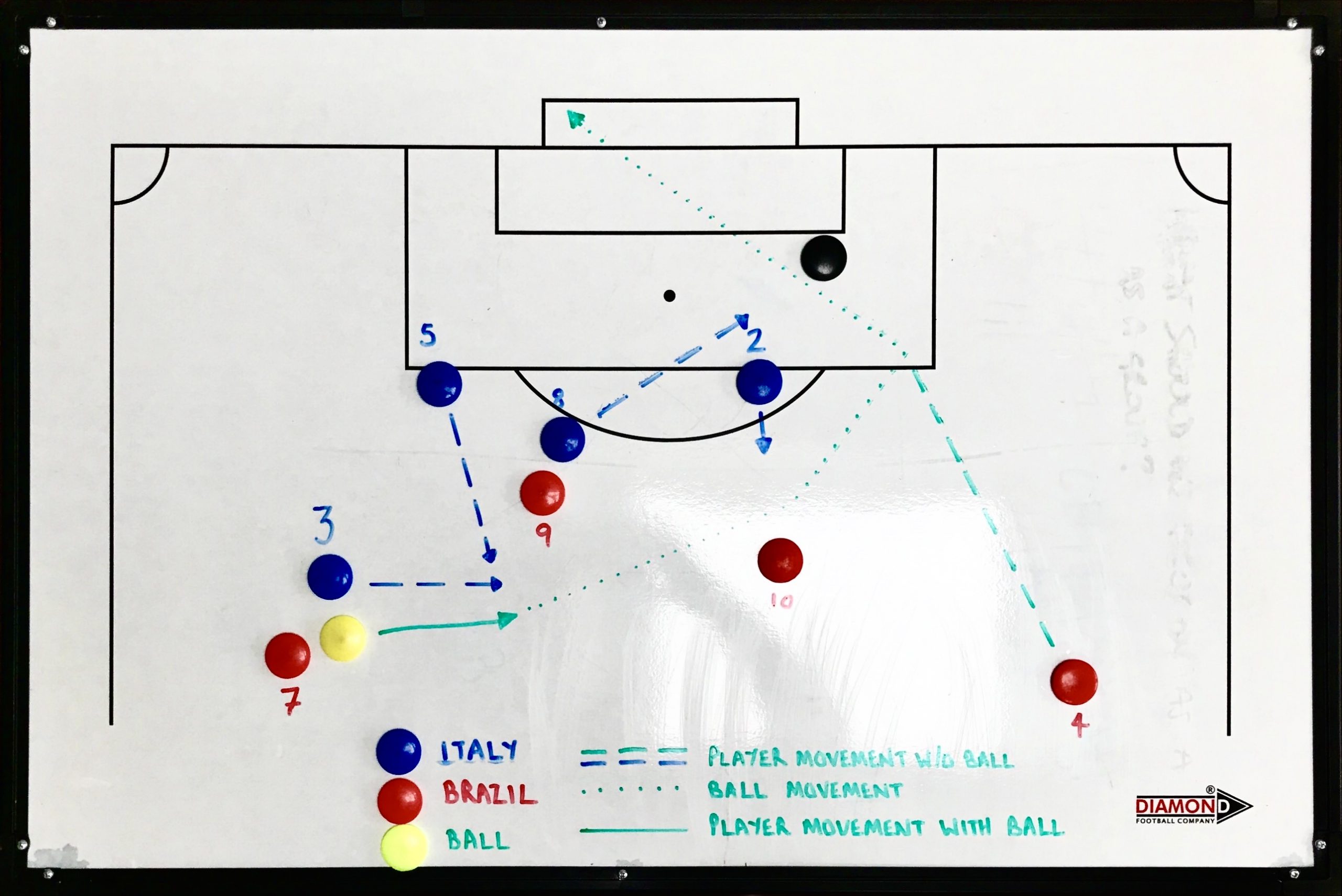

Using Zona Mista, the Italian defence might have looked more like diagram 3 in shape. Cera could have picked up Jairzinho, and Facchetti could have stayed marking the space on the left-hand side (or picked up the libero position from Cera). Diagram 3 thus shows, without Rosato or Burgnich having moved, a far more balanced and compact shape.

Alternatively, if Rosato had shuffled across to cover behind Facchetti, with Cera behind to cover both Tostão and the space behind Burgnich, then Burgnich might have had more confidence to go out and close Pelé down. From that position Cera might also have been able to block Carlos Alberto’s eventual shot. But of course, if Cera was eight yards further left when Pelé was on the ball then the Brazilian would never have dreamed of passing it to the corner of the penalty area as he did: he’d have played it further back; Carlos Alberto would have had to check his run; the Italians could have re-grouped and the goal may not have happened.

These are all ifs and buts, but it wouldn’t be long before they became more realistic propositions. As Jonathan Wilson wrote in Inverting the Pyramid, this goal represented the last time a team could play with such time and space at international level. By the time of the next World Cup, against any number of teams, Brazil would not have had it so easy.

Summary

The goal came about because of the following factors:

- Clodoaldo’s dribble dragged four Italians out of position, badly damaging their shape in midfield

- Jairzinho’s acceleration in front of the Italy back line finished the job Clodoaldo started, taking two defenders out of the game including libero Cera

- Burgnich’s failure to close down Pelé gave him the space to play his killer pass at his leisure

- The tiring Italian defence failed to adjust their rigid man-marking system to the match situation, leaving an enormous space on the right flank that Pelé and Carlos Alberto exploited to full effect.

Key points to take away

- From the Brazilians, we can learn that changes in tempo can be an excellent way to control the game. Possession doesn’t just have to be one speed – and mixing running with the ball with passing is one way to vary it.

- From the Italians, we learn not to be too rigid with your system. Have a gameplan, but don’t be so married to it as the Italians were with their man-marking catenaccio that you miss opportunities or fail to spot dangers.

- And finally, mental fitness is a by-product of physical fitness. If your body is tired, your mind will be tired. Make sure you can stay alert and think clearly for the full length of time needed.

Great analysis. The samba boys defined the peak of the “jogo bonito” in 1970.

It is a given the Italian team had a difficult game against Germany, however I want to mention the preparation Brazil did to play in the altitude. Brazil spent many weeks training at high elevations in Mexico to adapt the players’ bodies to the altitude where the oxygen levels are lower. Also, a tremendous study of the adversaries, with slides and deep analysis with coach and players before each match. In addition, we cannot forget that Brazil started a scientific physical training and metrics well advanced of other teams at the time. When one adds all of this together it can explain why the Italians seemed so tired and the Brazilians were playing as if the game had started. To prove my point, let us recap the previous games Brazil played. The second half was always the period where Brazil scored the most. It was not just Italy, all the other teams were victim of the heat and the thin air, while Brazil, based on its best team ever, had also the advantage of knowing the adversaries, better lungs due to the training in the altitude (more red blood cells=more O2), and the physical fitness.

Great points Eduardo, thanks for posting!